Record date:

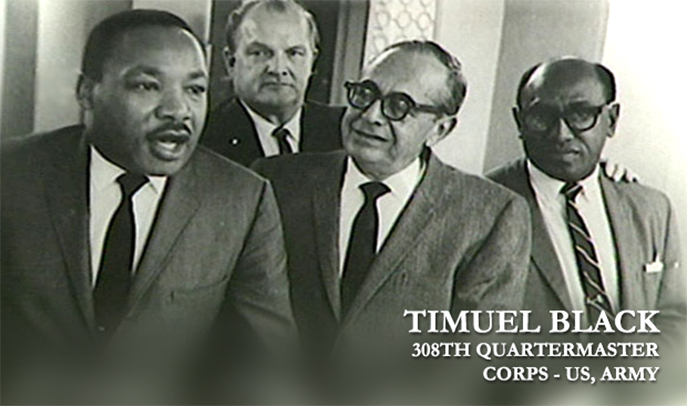

Timuel Black, PFC

At 101 years of age at the time of the interview, activist, historian, WWII veteran, Timuel Black, is an ongoing example of service to the American people. He continues to share his stories generously without either nostalgia or bitterness, in order to impart a message of hope to the young. For Mr. Black, the past should be recognized as well as the hard-won civil rights that were gained, while understanding the racial problems of the present day. As Black quotes in the Declaration of Independence. “We hold these truths to be self-evident”.

Mr. Black was born on Dec. 7, 1918 in Birmingham, Alabama. His parents had been indentured servants and in 1919, the family migrated to Chicago as part of the First Great Migration of African Americans from the South. They arrived shortly after the infamous race riots of that year to find that Chicago offered employment in the stockyards and steel mills, as well educational opportunities for the young that were unavailable in the South. Black reflects on growing up in “the Black Belt”, which was roughly the South Side of the city. Mr. Black’s father was a follower of Marcus Garvey and instilled pride in his young son, while his mother reminded him that he must seize any opportunity to better himself. His plain-spoken grandmother, who had been a slave, taught the young Timuel Black the value of irony and understanding.

The Black community faced the northern version of Jim Crow. But things like ‘restricted covenants’, i.e. agreements between property owners and sellers, not to sell to African Americans, and other types of overt and covert racism also had the effect of creating a community with parallel institutions in economy, culture, and everyday life. For example, Jazz, blues and gospel gave the Black community songs of love, resistance, and spirituality. Self-respect and educational aspirations remained high, even under the Great Depression. Mr. Black fondly recalls his personal associations with many of the great Black artists of the time, including legends like Nat King Cole who sat behind Timuel in high school.

Mr Black notes the systemic racism and class distinctions in the more “prestigious” Englewood High School that motivated him to transfer to Wendell Philips High School. Phillips put him into contact with several important figures in Chicago education such as the forward-thinking White teacher, Mary Herrick, who worked in tandem with Chicago Public Library’s first Black librarian, Vivian Harsh, who was also a co-founder of the teachers’ union. Unlike many Americans who were caught off guard by Pearl Harbor, these two educators had introduced their students to speeches of Hitler and Mussolini as far back as the 1930s. This exposure to fascism and the racist policies of the fascist states resonated strongly with students who were the children and grandchildren of slaves.

At a time when there was segregation in the forces and few Black units were entrusted in combat itself, Mr. Black served in the US Army in the 308th Quartermaster Corps, popularly known as the Red Ball Express. This service unit was deployed to England and landed on Utah Beach at Normandy just a few days after D-Day. Their mission was to drive trucks, non-stop, on roads which were not necessarily roads, transporting supplies and ammunition to combat units. Because of this vital role, those in the Red Ball Express were highly vulnerable to enemy attack, whose objective it was to cut off the flow of supplies. Black and his unit also witnessed first-hand the horrors of the Buchenwald concentration camp, in Germany, after it was liberated. Mr Black was awarded Légion d'honneur, [Legion of Honour], the highest order of merit, both military and civil, from the French government on his 100th birthday.

Mr. Black was asked a common question from other Allied soldiers, “Why do we see Negro soldiers under White officers and we never see White soldiers under Negro officers?” The universal attitude by the African American servicemen regardless of whether they volunteered or were drafted was, “We will straighten this out when we get home”. As Mr. Black concludes, “We returned home with a commitment that we were going to break racial inequality. That was the beginning, psychologically, of the civil rights movement. “

Mr. Black discusses the two cases on restrictive covenant cases. In Hansberry v. Lee (1940) it was ultimately judged illegal to bar African Americans from purchasing or leasing land in a Washington Park subdivision of Chicago's Woodlawn neighborhood. In the Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) case, the US Supreme Court struck down racially restrictive covenants, altogether. He cautions the interviewer to judge a person on his or her own merit, not according to race or religion. One should also resist the temptation to oversimplify, noting that Hugo Black [no relation], one the White judges of the Supreme Court who voted to end restrictive covenants, had been involved in the Ku Klux Klan in his youth, while a far more liberal judge upheld these same restrictions locally in Chicago.

Finally, Mr. Black movingly urges young people of all backgrounds to talk to their older relatives, not to blindly imitate them but simply because, “there’s an obligation to the truth, to the future.”