Record date:

Kenneth A. Hogan, Sergeant

With public attention on the Vietnam War, in 1966, Ken Hogan did not expect to find himself fighting in the demilitarized zone, DMZ, between North and South Korea. The close-range fighting that Sergeant Hogan and those of the 2nd Division experienced was a far cry from the purported warm-up to Vietnam. Sergeant Hogan’s oral history is conducted by General James Mukoyoma, then Brigade S-1 at Camp Young, the division’s headquarters in the DMZ. An informative interview with two perspectives is presented about the little-known “Second Korean War”.

Kenneth Hogan was born in Evanston, Illinois in 1941. Like family members who served in the armed forces before him, Hogan too felt that it was his duty to serve. With the spirit and the support of his wife and family, he was proud to be called to service in October 1966.

That being said, Hogan was surprised by the immediacy of his induction. At the end of a twelve-hour process of multiple tests and the swearing-in ceremony, he and the draftees were sent to Union Station, in Chicago, not to return home. Rather they would board trains to start their service. Because of Hogan’s random position in the lineup, he was sent to train as a US Army Infantryman rather than a Marine. After receiving his uniform at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, he was then sent to Fort Stewart, Georgia. There he did basic training and AIT, advanced individual training, becoming a skilled Infantry rifleman.

During the training, Hogan was positive that he would be shipped to Vietnam. At the last minute, new orders were received that he and his fellow soldiers would be deployed to the DMZ, as practice for Vietnam. The Korean War Armistice Agreement, of 1953 established a demilitarized zone or strip between North and South Korea, north of the Imjin River. Increasing incursions and attacks by the North Koreans required US Army reinforcement.

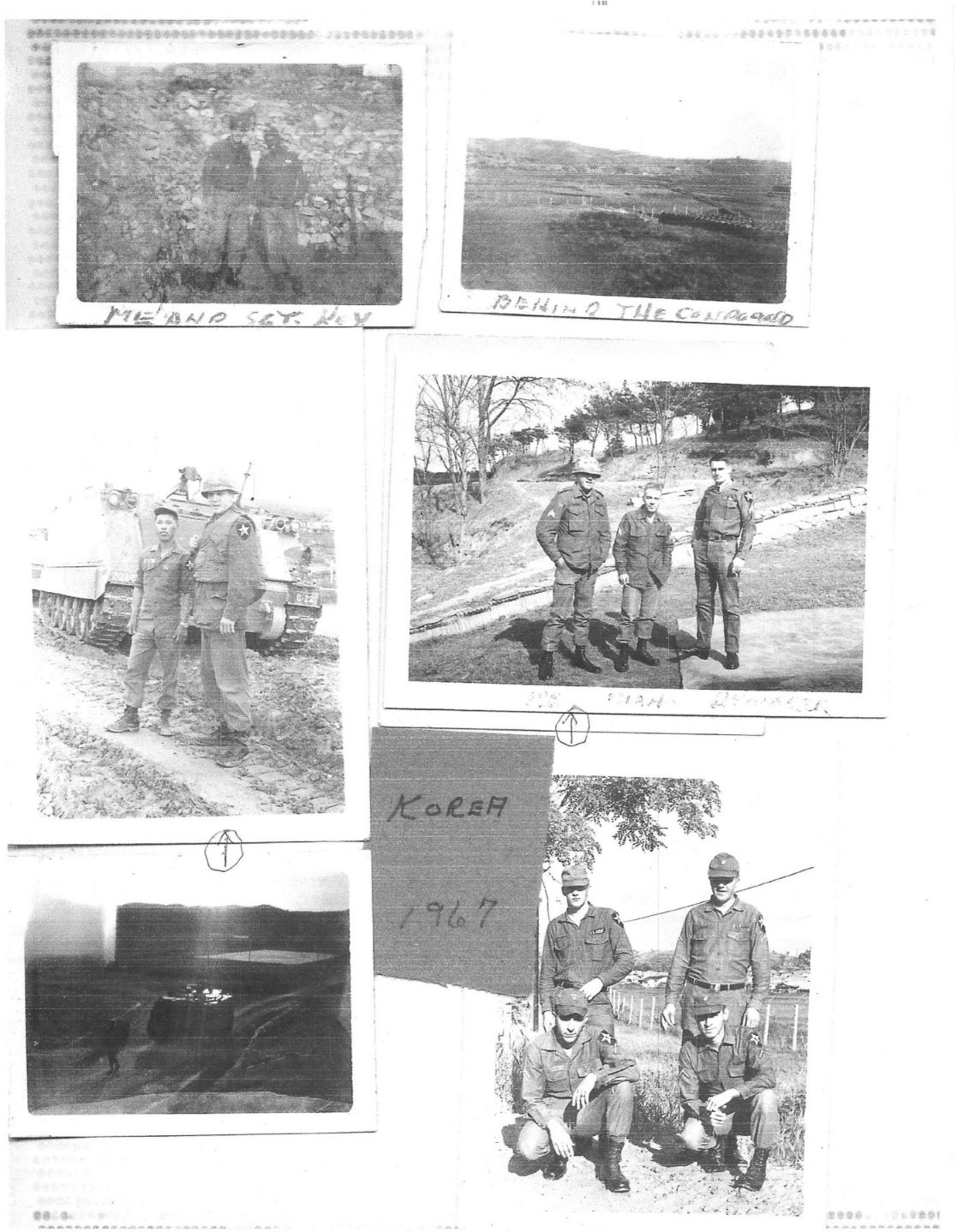

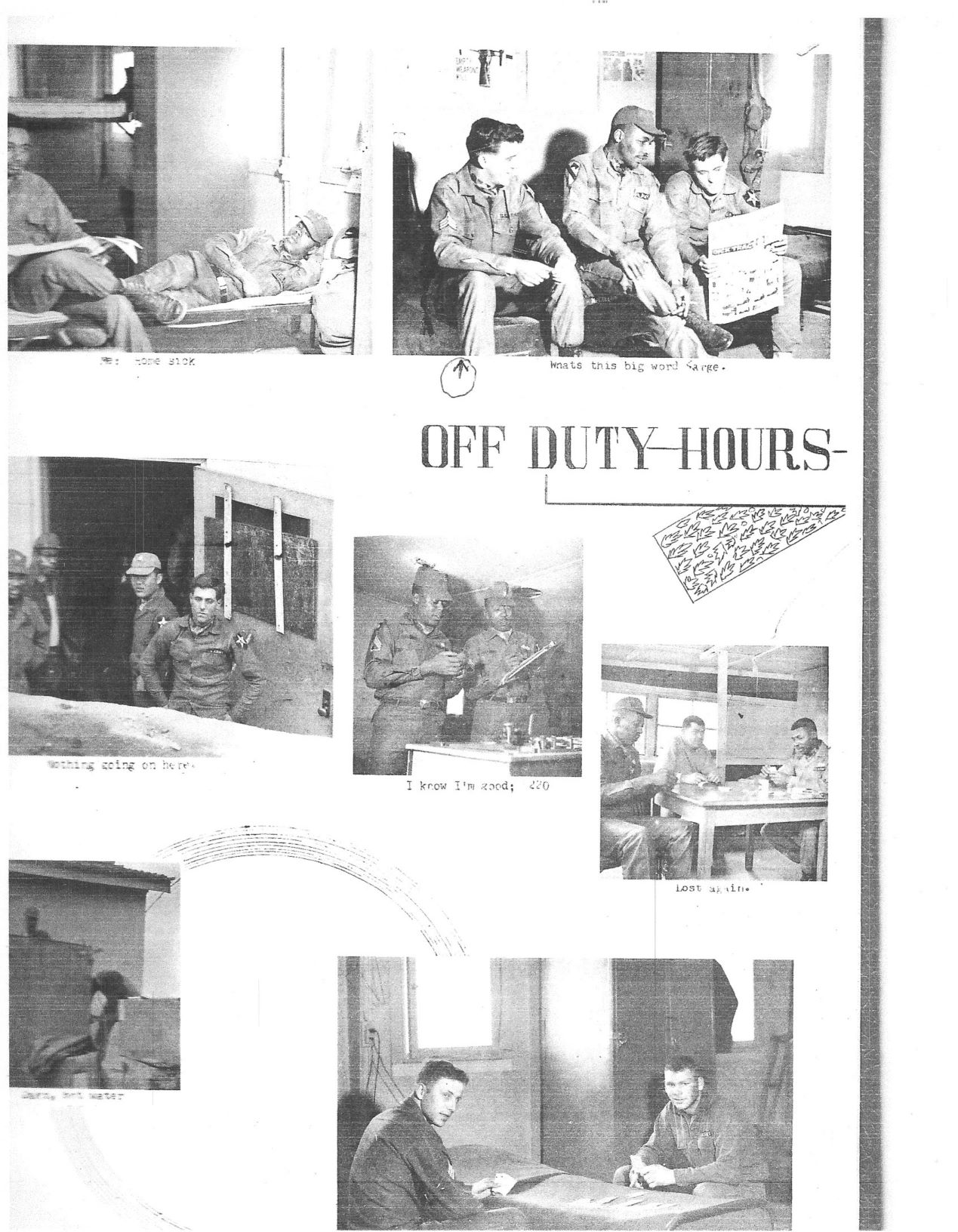

Hogan was assigned to the 2nd Infantry Division, 23rd Regiment, 2nd Battalion. His unit was at Camp Greaves. On his very first night in Korea, he was sent on patrol to the DMZ sans intel. He found already well-fixed positions like foxholes or trenches, indicating to him that the conflict was not merely a temporary flare-up. Indeed, it was ongoing, and he could hear bullets whizzing through the nearby trees.

At first, his battalion was located at a base south of the Imjin River, and they would be trucked into the DMZ for patrol. Then they were situated in the DMZ itself, north of the Imjin River. General Mukoyama, who was then responsible for planning his battalion’s movement north, explained that this was a result of the conflict heating up further.

Sergeant Hogan battled in multiple firefights against the enemy. North Korea’s elite troops were known for their cruelty, and he was shocked by the excesses that he witnessed. One night, Hogan and his men were zoned in on by the enemy at a moment when the latter was intent on retaliation. The North Korean soldiers were so close that Hogan and his comrades could smell their kimchi rations. He saw bullets heading in his direction and heard the sounds of them chewing up the concertina wire around them. Hogan could even hear the enemy pulling the pins from their “pineapple” grenades which landed so closely that he and the men were covered with dirt. In Hogan’s prayer to God for life, he vowed not to kill the next enemy soldier who would appear in his rifle sights. Within minutes, he was face-to-face with a North Korean soldier. Miraculously, neither one pulled the trigger. Due to illumination caused by the activation of the trip wire, other US soldiers nearby saw the predicament, opened fire, and “took care of the guy.”

Hogan made it through that night and the rest of his tour in Korea. Even back at home, Hogan has been haunted by nightmares where he can still see this man’s face though they have lessened in his senior years. He appreciates his late wife who stood by him.

He also expresses disappointment that their battles were unknown by Americans due to censorship of letters, minimal coverage by general news media, and the government’s desire to keep it quiet in light of the growing controversy over Vietnam. Even the military needed some “prodding” in recognizing that DMZ fighters should qualify for the Combat Infantry Badge and for combat pay. General Mukoyama had initiated the paperwork for this necessary recognition.

Next, Hogan returned stateside to Fort Hood, Texas in order to learn riot control. He was sent to Great Lakes Naval Base, Illinois in preparation for the expected unrest at the 1968 Democratic Convention. Ultimately, Hogan was not sent to Chicago and was honorably discharged from his service at Fort Hood in 1968.

After Hogan’s military service, he returned home. Grateful that his wife had kept up the mortgage payments, he decided that it was now his turn to work right away. The two also wanted to start a family, in time having three children. Hogan feels fortunate that he could return to his former job as a heavy equipment operator at the Village of Morton Grove. A few years later, he became superintendent, in charge of the street department, and there he worked for thirty-two years. He declined other offers such as recruitment by the FBI.

Unfortunately, Hogan was compelled to have a lung removed in 2007. Although it took three years, the VA eventually accepted his claim that his cancer was due to his exposure to Agent Orange, widely used in the Korean DMZ. Sadly, these same chemicals have also caused Ken to suffer from COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and he is now in hospice. Still, Hogan has nothing but praise for the excellent medical care provided by the VA.

This modest man of faith shares these inspiring words:

“[A] Citizen Soldier... is [there] to protect our faith, protect our way of life, and to make sure that anybody who tries to put it down … [is stopped] … I hope I have strength enough to still do something. He gave me the strength back when I was a soldier.”

He also welcomes contact from his comrade-in-arms.