Record date:

Seymour Nussenbaum Transcript.pdf

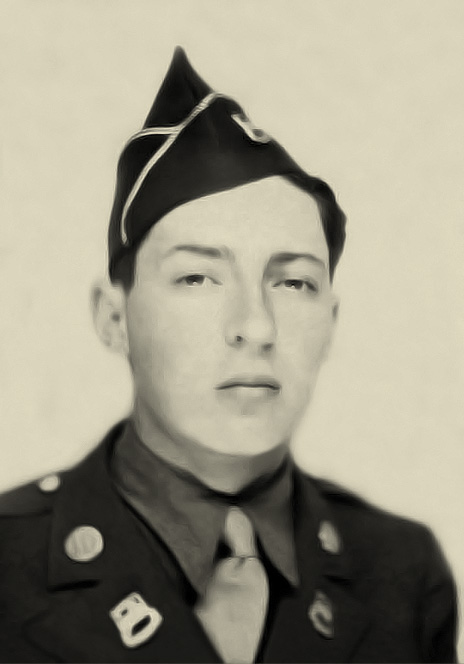

Seymour Nussenbaum, PFC

As Private Nussenbaum (ret.) used to say of his WWII service, “I blew up tanks”. Indeed, as part of the 603rd Camouflage Engineer Battalion, 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, known as “The Ghost Army,” Nussenbaum blew up inflatable rubber tanks, intended to deceive the enemy.

Seymour Nussenbaum was born in 1923 in the Manhattan, New York City. His passions for art, Judaica stamp collecting, and paper emerged when he was a child. His father succeeded in supporting the family during the Depression though it was a struggle - often working on evenings and weekends. At DeWitt Clinton High School, Nussenbaum was on staff of its publication, The Magpie. After graduating high school at age sixteen, he began to work as a delivery boy in the garment industry and studied art at Leonardo Da Vinci School of Art during the evenings. Realizing the need to sharpen his craft further, Nussenbaum enrolled in the Pratt Institute in 1940. There he signed up for a non-credit course on the art of camouflage figuring that he would soon be drafted.

Nussenbaum was motivated to contribute his part in the fight against Nazism both as an American patriot and as Jew. His paternal grandparents were trapped in Europe. In February 1943, he found himself assigned to field artillery, in spite of having taken the camouflage course. Persistent, he wrote a letter to the authorities and was indeed transferred to 603rd Camouflage Engineers.

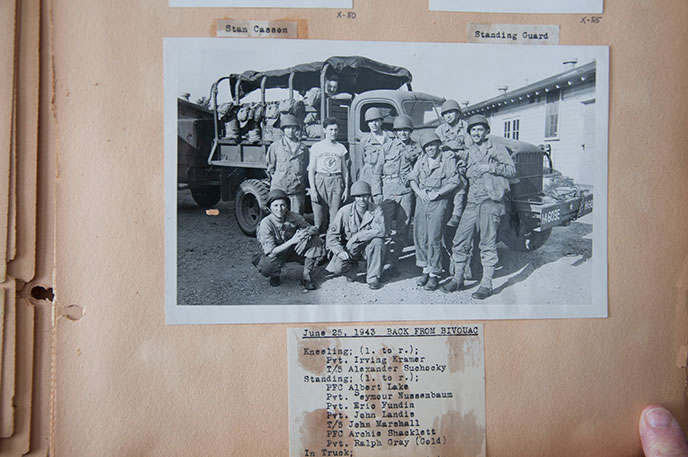

During their training, either at Fort Meade or at Camp Forest, Tennessee, the unit made dummy army vehicles out of wood, burlap, and later rubber. Nussenbaum explains the purpose:

“…the idea was to fool the enemy about where our troops were… Let's say you had one division in one spot, and he [i.e. you] wanted to move it thirty miles or forty miles down south and you don’t want the enemy to know they moved…. So, we would come in with our rubber tanks and … put them in the same spot where their real ones were...” Pp. 7-8

In May 1944, Nussenbaum and his unit were shipped out on USS Henry Gibbons, wondering if vibrations they felt were a result of US set depth charges or whether they were being torpedoed. When landing on the western coast of England, the Germans were strafing the ships, so Nussenbaum and the others went under the deck to avoid being hit by bullets and shrapnel. In England, the unit was living in tents on the grounds of Walton Hall, a manor requisitioned by the Army. One day, they were woken up to thousands of planes in the sky heading east which they later found out brought paratroopers to Normandy. Nussenbaum and his group landed on Omaha Beach about three weeks after the invasion. They immediately climbed the cliffs and were told to dig foxholes in the ground for the night. Going through the recently conquered small towns near the English Channel, such as Saint-Lô, Nussenbaum was shocked by the destruction. He and the unit were often on the move in France, transporting dummy vehicles on their trucks in addition to a trailer carrying a dummy bridge, with little time to reflect nor to sketch. He also participated in special effects or atmosphere deception. For example, four to six guys would sit at the edge of a truck so that it would appear to have the maximum capacity of passengers. The truck would circle around town, changing the number on the bumper each time, as to give the impression of military strength.

Nussenbaum and others were also instructed to frequent bars and give out specified false military information as to confuse the enemy, should there be local Nazi sympathizers, overhearing these conversations. Many of Nussenbaum’s efforts were related to the printing of false patches. If one is pretending to be part of a division, one needs to wear the patch of that division. An original patch would be traced. Then a template for each color would be cut since each color could only be printed separately, a process that was lengthened by the fact that it took time for each color to dry. He estimates that 30, 000-40,000 fake patches were made of real divisions. While stationed in Luxembourg in October, 1944, Nussenbaum and the others used their creativity to put on a talent show. In December 1944, Nussenbaum and others heard that there was “something” going on in the north, which they later discovered was the Battle of Bulge, but they were sent back to Verdun in northeastern France.

A few months prior, that Nussenbaum attended Rosh Hashanah service, led chaplain Rabbi David Max Eichorn, in an empty synagogue in Verdun:

“It poured that day…they had given us an option if we wanted to go to services, …so I went and it was very touching, because there were about four or five hundred of us…standing…with the roof was leaking. It was cold, but nobody complained… towards the end of the service, [we] started to sing Hatikvah...”

That being said, Nussenbaum could not escape the needling antisemitism of his first sergeant, who constantly assigned him on KP or sent three Jewish soldiers out of four, to check if a village was clear of Germans.

On VE Day, May 8, 1945, each soldier of the unit was given a different bottle of wine, from a captured cache of liquor. Afterwards, the Ghost Army was stationed at [Wiesbaden] Idar Oberstein, in the southern part of Germany, where the Army tried to find things for them to do now that their mission was over. They also helped with the distribution of rations in DP Camps. Through his travels around the Rhine with his German and French speaking Army buddy, Helmut Eisenberg, the curious Nussenbaum met older Germans who hated Nazism. Nussenbaum had heard about concentration camps since the troops circulated pictures of but did not know then the fate of his relatives until later.

He and the unit were sent back to a debarkation camp from France, from which they were shipped back to the US, Newport News. From there, they were sent to Fort Dix, NJ. Since the war in Japan was still on, they were given one month’s leave at home until reporting to NYC, from which they were sent to Camp Pine, New York. Because Nussenbaum was missing one point needed for discharge, he was sent to Camp Shelby, at Hattiesburg, Mississippi for one last month. Happily, VJ Day arrived, and Nussenbaum was discharged. Before leaving, the group was told to keep their work in the Army secret for fifty years.

Since it was already November 1945, when he returned to NYC, Nussenbaum was to wait for the next semester at Pratt to resume his course of study. He then compiled scrapbooks of ephemera, now at the WWII Museum, that he had assiduously collected throughout the war and mailed home.

Between the semesters, he found a job as an arts and crafts counselor at a summer camp. There he met the woman who would become his wife, Vera. Nussenbaum relays her moving story of being sent on a Kindertransport from Leipzig to England, fostered by a kind couple there, until her uncle brought her to the US, her mother having perished.

Although Nussenbaum had aspired to become another Norman Rockwell, he felt that he did not have the talent for it and began what ultimately became a satisfying career in package design, working many years as a company’s art director. Through Ghost Army author and filmmakers, Rick Beyer, who interviewed him, Nussenbaum enjoyed the opportunity to meet his friends from over seventy years such as Bernie Bluestein, also interviewed by PMML.