Record date:

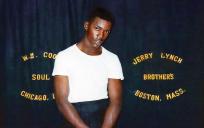

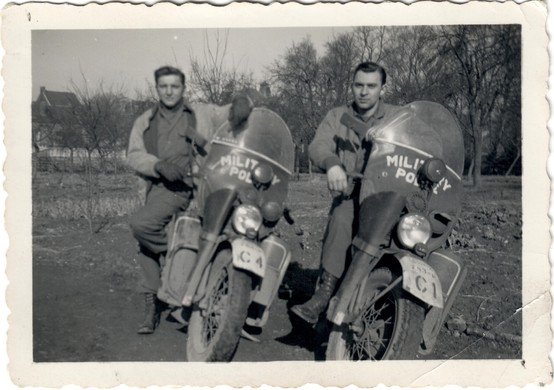

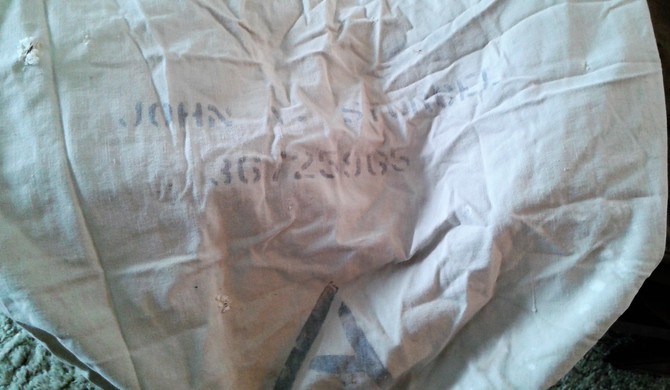

John Storcel, PFC, Military Police

From the chaotic amphibious Invasion of Normandy to the grueling Battle of the Bulge, John Storcel has seen a magnitude of the horrors of war during his service in the 783rd Military Police Battalion.

Storcel was born in what is now Slovakia, formerly part of the now dissolved Czechoslovakia and immigrated with his family to the United States. The family settled in Chicago when he was six years old. He had four siblings, but one sadly died at only 18 months old shortly after the family arrived. His father served in the Austrian-Hungarian Army during World War I, an experience he didn’t discuss with his children. Storcel’s father was badly injured in the war and forbade the discussion of war at the family’s tavern. Unfortunately, Storcel’s father died at forty-nine in 1940, leaving him to help his mother run the family business.

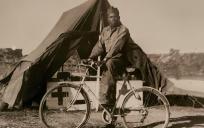

Despite being the breadwinner of the family, supporting his mother, and contributing to the war effort building valves for US Navy ships, Storcel was drafted in 1943. He was sent to Fort Custer in Michigan for basic training and later to Pine Camp, where they conducted mock battles and trained officers. He performed several other duties stateside, including traffic control, evening patrol and controlling other service members while on night leave. Storcel also spent time on the east coast because he believes the nation was preparing for a possible invasion from Nazi Germany.

Storcel eventually went to Plymouth, England, to help prepare for D-Day, where he guarded coal piles and prisoner transportations. While crossing the Atlantic on his way to Plymouth, though, he and the other MPs grew tired of the conditions, particularly the lack of hot water. Their cabin was next to an officer’s quarters, which had hot water, so Storcel and his friend, Bill Uliks, found and turned the valves that controlled the water flow. However, while they were turning the valves, the siren for drills went off and in the rush to get outside, they forgot to turn one off. This flooded their cabin with hot water. The jig was up.

During and after D-Day, Storcel performed various duties, but none more gruesome than collecting dead soldiers at Normandy Beach, Saint-Lô and the Battle of the Bulge. To ensure fallen soldiers in body bags could be identified, they’d leave one dog tag with the body and another on top of the body bag. Often, though, the bodies were missing limbs. So he and the other MPs would have to find the dead soldier it belonged to and place them in their body bag. Sometimes this was done carelessly by others, Storcel says, as some MPs just placed random limbs in random body bags.

To hear Storcel's recollection of the D-Day leading, click here.

Storcel had volunteered to General Patton’s Army toward the end of the war but he was held back after his friend, Bill Uliks, who he calls the “greatest person on Earth,” told his commanding officer that he financially supported his mother. He returned to the States, got married, had children, and found stable work as an electrical contractor and business owner.

Storcel considers himself a patriot, is proud of his service, and is a member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion. However, he is critical of the United States military and its “blunders” during the war, which cost young men their lives, he says. A regret that he truly bares is a broken promise to his father. On his deathbed, Storcel’s father made him and his brother promise him that they would not go to war.

“But when I was drafted; what was I gonna do? So… I… I lied to him. I went to war,” Storcel says. “So that bothered me quite a bit… And he died at the age of forty-nine. But that bothered me.”