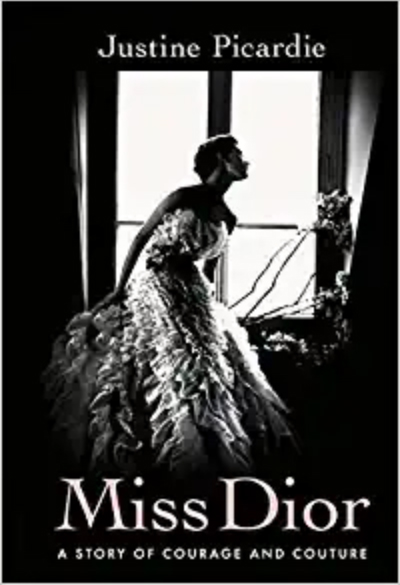

Miss Dior: A Story of Courage and Couture

Miss Dior: A Story of Courage and Couture

by Justine Picardie, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2021, nonfiction, 438 pages, magnificently illustrated, some color

Justine Picardie, former editor-in-chief of Harper's Bazaar UK and Town & Country UK and former features director of British Vogue, whose previous works include Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life, has written a richly rewarding book. Miss Dior is the biography of Catherine Dior, reticent sister of the famous couturier Christian, a seamless weave of couture and war, money and the human spirit, the demands of memory and the share oblivion requires. Perhaps only Picardie, daughter of a father born to Jewish parents in 1936, many of whose relatives died in the murder pits and extermination camps, and herself a fashion journalist, could have done so much justice to Catherine Dior.

Dior, a discreet and honorable former intelligence officer, was a challenging subject. Picardie had to assemble the known facts, then resurrect Dior, in a splendid exercise of historical imagination that was richly informed by her own life in the long shadow of the Holocaust and her knowledge of the art and craft of high fashion. Picardie’s sources include site visits, access to the Dior archives, the memoirs and observations of Dior’s friends and contemporaries, and a wealth of illustrations, ranging from family photos to drawings by German concentration camp survivors and fashion illustrations.

Born on 2 August 1917, when France was heavily engaged in the Battle of Passchendaele, Catherine Dior was some 12 years younger than her brother. In the spring of 1940, France was again at war with Germany, and although her generals failed her, the French Army went down fighting. During the Fall of France from 10 May to 22 June 1940, some 90,000 French soldiers were killed, another 200,000 wounded and some 1.8 million were reported missing.

In a France in which women had no say in the laws that governed them, Dior was not a soldier. (It matters to know that Frenchwomen were only allowed to vote in 1944 because of their roles in World War Two. That they created the French people, often dying and commonly suffering permanent injuries in the process, while doing unpaid but utterly vital domestic labor, was used as an excuse to disenfranchise them, rather than understood as why the franchise inhered in them.) However, Dior became a résistant while Christian did not. Formally. He was deeply loyal to his sister and her vision of France, so he allowed her to use his Paris flat as a base for herself and her comrades—to the dismay of some of his other friends. Each did what came to them to do, that they could.

After the Fall of France, Catherine’s rejection of the German occupation led her in search of a battery-powered radio. She wanted to listen to BBC broadcasts, including those of the exiled leader of the Free French, General Charles de Gaulle. Her search led her to a radio shop in Cannes managed by Herve des Charbonneries. He was born in 1905 like Christian, and married to Lucie (née de Lapparant), who gave him three children. Rejecting, perhaps together with de Lapparant des Charbonneries, the paternalistic codes of France that mandated women be dutiful daughters, then virtuous wives, Catherine embarked on a life-long love affair with Herve. She did not, however, marry him. For his part, while des Charbonneries and his wife never divorced, their separation was said to be amiable, and he kept faith with Dior until his death.

Both des Charbonneries were members of F2, a French resistance network with strong ties to both British and Polish intelligence. By at least November 1941, Dior herself was also a member whose responsibilities would include transmitting reports to London. Arrested on 6 July 1944, Dior was arrested and so brutally tortured by a ring of French collaborators known as the Rue de la Pompe Gestapo that they destroyed her fertility. She was initially reported to have died under torture. The French Resistance considered their fighters to have done their duty if they could keep silent for 24 hours under interrogation, but Dior never broke. Her indomitable fortitude saved many, including both des Charbonneries. On 15 August 1944, despite her brother’s desperate attempts to exploit his German contacts to save her, she was deported to Germany on one of the last trains out of France. Dior survived slave labor in Ravensbruck and other camps, a death march to Dresden and likely rape by Soviet troops during liberation. When Dior returned to France on 28 May 1945, she was so emaciated her brother did not recognize her and too sick to eat the celebratory dinner he had prepared for her.

A Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, Dior’s significant decorations included the Croix de Guerre, normally reserved for regular soldiers; the King’s Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom; and the Cross of the Resistance Volunteer Combatant. A post-war photograph of Dior in the uniform of the Forces Francaises Combattantes reveals a woman who has survived Hell but not left it behind. Like many survivors, Dior barely spoke of what she had endured. Speaking of trauma can be traumatizing in itself: oblivion must have its share. Like many survivors who had endured that which on ne peut pas nommer, she craved solitude.

For good reason. One of Dior’s few public statements about her suffering was her testimony in the November 1952 trial of the Rue de la Pompe Gestapo. When she identified Théodore Leclerq as one of her torturers, his lawyer insulted her by insisting she had mistaken him for two different men—one of whom was 10 years younger, and of Iranian, rather than French, ethnicity.

These were the men and the woman who had tortured Dior and her comrades, some unto death, deporting the survivors to the unimaginable horror of the German camp system. And yet the sentences were pathetic: only eight of the 12 French were sentenced to death and just three were executed. Three men received life sentences of hard labor, and the one woman torturer, 20. The German SS officer who had supervised the torture at the Rue de la Pompe received five years, his German assistant just three.

As a résistant scratched on a cellar wall of the Rue de la Pompe with their nails, “We have been tortured by the French people.”

****

Occupation and the need to survive occupation—and all the many levels of collaboration that survival requires—damages, even fractures a society for generations.

Confronting this reality leads Picardie to the weakest section of the book, a long passage about the American socialite Wallis Simpson. Suffice it to say that Simpson and her husband, the former King Edward VIII of England, were widely suspected of Nazi sympathies. Simpson’s own words strongly indicate she was an American racist—from which German Nazis learned a great deal. In 1951, Simpson, who in today’s parlance was an unparalleled influencer, became one of Christian’s clients. One cannot read this without thinking Picardie’s editor should have helped her clarify the complex issues involved in this client relationship, precisely because it is critically important to understanding the post-war France that Dior soeur er frère had to navigate.

The world knows Dior through her brother Christian. He defined post-war fashion with his first collection for his own house, a “New Look” that bid farewell to wartime rationing and austerity when it debuted on 12 February 1947. Christian had hinted at what was to come in his work for his final employer, couturier Lucien Lelong, in the Théâtre de la Mode exhibit of 1945-1946. The Théâtre de la Mode was meant to jumpstart a mainstay of the French economy, haute couture and its simplified, accessible version that is ready-to-wear fashion

The Théâtre’s success exceeded the economic: its extraordinary imagination and exquisite craftsmanship were a release from ugliness, a resurrection of beauty in the aftermath of occupation and the épuration sauvage. In this wild, unofficial purge, Frenchwomen were punished for consorting (“horizontal collaboration”) with Germans by having their heads shaved, and being stripped, beaten, spit upon or stoned, tarred and feathered, even murdered. Very few of these women were guilty of any serious collaboration. Indeed, some of their “crimes” had been to be raped by Germans or to sell them sex to feed themselves and their children because Frenchmen refused to employ them at “male” wages. While their overwhelmingly male attackers were sometimes real collaborators themselves, eager to cleanse themselves of their shame by inflicting it, and real damage, upon a woman. Indeed, Frenchwomen returning from the German camps with shaven heads were often attacked as femmes tondues. Soviets were not the only men who attacked women victims of the Germans.

Many of these collaborators were themselves a long way from those in the Rue de la Pompe, even as they may have provided such people with victims. In turn, these were different matters from the collaboration of men like the viciously anti-Semitic writer Louis Ferdinand Celine, or the couturiers Jacques Fath, who attended soirées at the German embassy, and Marcel Rochas, who ostentatiously avoided his former clients when they were marked as Jewish.

No shaven heads for them: they all participated in the Théâtre de la Mode.

Along Christian, a small, plump gay man whose smile reflected his shy, private, kind, and gentle nature, who kept dirty company simply to survive in his calling while he sought his sister, or news of her murder. His was yet another type of collaboration and different still from that which his friend and colleague Pierre Balmain remembered. They were watching a showing for the wives of French industrialists and prominent black marketeers, “Just think! All these women going to be shot in Lelong dresses!” Christian observed.

In this context, his New Look was not simply a repudiation of the lean modernism of the 40s.

In his own words, Christian designed for “flowerlike women, with rounded shoulders, full feminine busts, and hand-span waists above enormous spreading skirts,” yet his New Look was free from “the degeneracy of elaborate decoration” and deeply rooted in French design history. Coco Chanel frankly called the New Look reactionary. Author Francine du Plessix Grey, whose diplomat father was killed in action in 1940, trying to join the Free French Forces, wrote with scathing honesty. “It turned the clock back to the restrictive folderol of La Belle Époque… and evoked alarmingly regressive models of femaleness: women as passive sex objects, displayers of their men’s wealth and status—women who needed huge trunks to travel with their finery and maids to help them dress.”

All this is true and yet it is not the whole truth of the New Look. This modern, fresh version of the Belle Époque of Christian’s childhood was not merely an escape from wartime austerity, but also the ugly moral corruption of France during the Occupation. And it was an aching lament for idealized feminine beauty and the hope of its resurrection, for the lost beauty of the brave women Christian knew or would have known of.

Beauty lost not to time, but to deliberate and unnecessary human cruelty.

The beauty of “Tania, Comtesse de Fleurieu, a brave woman in the Resistance. She had been very lovely but now all her teeth were smashed. They had beaten her across the mouth. She knew about Lili (Elizabeth), she had been there, in the same hut. Beaten, degraded, and too broken to move, Lili had been dragged from her plank bed by the hair of her head and thrown into the oven alive. She died because she had borne my name, there was no doubt about that…” So wrote Philipe de Rothschild, who had joined the Free French abroad, of the terrible death of his wife Elizabeth. At a fashion show, she refused to sit beside Suzanne Abetz, wife of Otto, German ambassador to Vichy France. She too, did what it came to her to do.

And the less physical beauty of women like Christian’s younger sister, Catherine.

Who lived in a country where men had chosen to purge the shame of their behavior under occupation by brutalizing women who had done less. A country in which her brother, a good and loyal Frenchman, would work hard to acquire a Nazi sympathizer as a client. A country in which her niece Francoise married leading British Nazi Colin Jordan, and neither of them were utterly ostracized for their ex post facto treason.

As de Rothschild quoted an anonymous woman, collaboration had been so much more chic than resistance.

How did Dior live, how did her brother live, knowing this?

This is how.

After the war, both Dior and des Charbonneries needed to earn a living, so they became sellers in cut flowers, especially roses, lilies, and jasmine. Dior rose at 4 am every morning to go to the flower market at les Halles. Even though she suffered from agonizing physical and psychological pain, a legacy of her torture and imprisonment, she never complained. Later, Dior would inherit her father’s farm and from there she supplied some of roses and jasmine that are the backbone of the French fragrance industry.

And this is also how.

Dior was not not even remotely Christian’s muse, that idealized invocation of male sexual desire. She was not a fashion plate, even though Christian would later name at least one exquisite dress for her and give her outfits from each collection. Even though after Christian’s death in 1957, Dior was acknowledged as his moral heir and custodian of his legacy. She had her own quiet style, armored not in her brother’s clothes to participate in the fashion cliques, but in the silence and courage for which she had paid such a ferocious price. And perhaps her own understanding of the price her brother had paid to survive, and to attempt to protect her and others. This is true even though he named for her the perfume Miss Dior, redolent of the Provençal jasmine and roses they both loved.

Miss Dior is a perfume of love, not sex. The love of brother and sister; the love of a woman and her man, which endured to the end; the love of a woman for her country and her land, a love that led her to a hell from which she returned without ever truly leaving.

For Dior was something altogether more important to her brother than a muse. She was Christian’s heroine, his beau sabreur, the handsome swordsman—beautiful and brave and yes, deadly to the enemy of her country and the land she so loved—however seemingly inappropriate it is for a woman to be this, even to other women, let alone to a man, least of all a kid sister to her big brother, a younger woman to her older lover. Even now, much less then.

It is the role of biographers and their editors to reveal the secret and silent truths of their subjects and their times, in order not to strip them naked in the public square, but to reveal their hidden motivations and thus perhaps help us understand our own and our times.

The one weakness of Miss Dior is that Picardie does not quite dare to reveal that inappropriate truth that may have lain at the heart of the siblings’ relationship. And yet, it is hard to fault her lack of daring in what is otherwise a splendidly imaginative work of military and fashion history.

Book essay contributed by Erin Solaro. Erin Solaro is the author of Women in the Line of Fire: What You Should Know about Women in the Military (Seal Press, 2006) plus stacks of unpublished and unfinished fiction.