1970 to Present

Direct U.S. military involvement ended in 1973 with the signing of the Paris Peace Accords, and the war reached its final resolution in 1975.

As the U.S. continued its efforts to expand, equip, and train South Vietnam’s forces and to gradually assign them an increased combat role, the numbers of U.S. troops in Southeast Asia were steadily reduced. By the end of 1970, American ground forces had participated in their final major operation of the war and their total numbers stood around 330,000. A year later, that number had been reduced by more than half to 150,000.

The peace talks originally begun in 1968 progressed slowly until January 1973, when representatives of the United States, the DRV, the RVN, and South Vietnam’s Provisional Revolutionary Government met in Paris to sign the “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam.” Negotiated primarily by U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and North Vietnamese politician Lê Đức Thọ—who were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts—the Paris Peace Accords of 1973 ended direct U.S. military involvement and resulted in a temporary ceasefire between North and South.

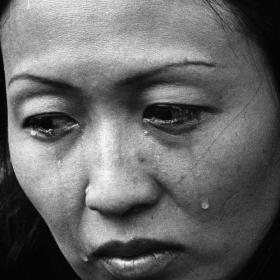

With the U.S. no longer standing in its way, North Vietnam quickly began to rebuild its military infrastructure and to reestablish its vital supply lines to the south. In March 1975, the PAVN and the Viet Cong launched a large-scale series of attacks that quickly overwhelmed the South Vietnamese defenses, and on April 30, the capitol city of Saigon was captured. In its final act of non-military aid, the United States helped evacuate more than 130,000 refugees whose lives were at risk in South Vietnam. With martial law in effect, many more would lose their lives trying to escape.

In the years immediately following the war, more than one million South Vietnamese were forced to enter reeducation camps, where they were imprisoned for years without formal charges or trials. A million more, mostly city dwellers without direct ties to the military or government, were forced from their homes to the jungles, where they were made to develop farmland. Tens of thousands were tortured or killed. As a result of these practices, some two million “Vietnamese Boat People” fled their homeland between 1975 and 1995, seeking asylum in neighboring countries and leading to a humanitarian crisis that ended with more than half of the refugees being resettled in the United States.

Today, after decades of reforms that began in earnest in 1986, Vietnam’s economy is one of the fastest growing in the world. The Vietnamese government has established strong dipolomatic relations with the United States, even allowing American citizens—including Vietnam War veterans—to visit recreationally. Meanwhile, the Vietnamese-American community has prospered in the United States, with thousands serving in the U.S. military—including U.S. Army Brigadier General Viet Luong, who in 2014 became the first Vietnamese-born general in the history of the American armed forces.