History of Vietnam

Long before American officials ever considered the issue of Vietnam, the nation was forging a path towards independence

On December 31, 1964, there were 23,300 American soldiers in Vietnam. Exactly one year later, there would be 184,300 U.S. troops in Vietnam. Despite this massive commitment of forces, many in the United States knew very little about the land their boys were being sent off to. Vietnam is first and foremost a war for many Americans and a country second. Yet, the history of the country and people of Vietnam helps explain the problems encountered by the French and subsequently the United States in their efforts to control the country.

The Setting

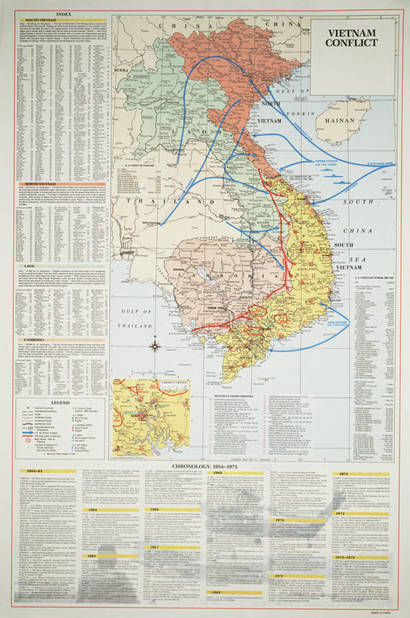

Modern Vietnam is situated along the South China Sea, stretching for more than 1,500 miles as it curves in an “S” shape along the coast. It shares a northern land border with China and western borders with Laos and Cambodia. The nation has an area of 127,881 square miles, roughly the size of Japan. Despite this, it is a thin nation – at its smallest, its width is only 30 miles. Vietnam is largely a homogenous nation but it does have a few significant ethnic minorities, including the Degar people of the Central Highlands, whom the French would call “Montagnards” or “mountain people.”

Early History

It is in this environment that the Vietnamese people lived, fought, and thrived. The Vietnamese were an established ethnic group by 200 A.D., but they were neither united nor independent. Primarily based in the north of modern Vietnam, the Vietnamese were but one people competing for power in Southeast Asia. From about 200 B.C. until 938 A.D., Vietnam was ruled by a succession of Chinese emperors. After defeating their imperial overlords, the Vietnamese began to consolidate their nation, though near constant conflict with the Chinese, the Khmers (native Cambodians), the Chams (the people of Champa, a southern kingdom), and fighting between rival Vietnamese rulers kept the nation weak. By 1428, a period of Chinese occupation was ended by a native Vietnamese rebellion, and the commander of these rebels became ruler of Vietnam. Establishing the Lê Dynasty, this dynasty would defeat the southern Champas kingdom and establish Vietnamese rule fully to the south.

However, internal discord broke apart the kingdom by the late 1500s, splitting Vietnam between the northern Trinh and the southern Nguyễn. It was in the 1500s that Europeans first began to arrive: Portuguese sailors arrived in 1516, and Catholic Dominicans missionaries followed in 1527. By 1580, Franciscans had arrived, and Jesuits arrived in 1615. While European trade with Vietnam continued, these Catholic missionaries converted thousands (especially in the north) and continually increased the European presence in Vietnam. Over time, these Catholic missions would increasingly be led by the French.

French Involvement

A rebellion in the late 1700s nearly destroyed the southern Nguyễn clan, but one survivor of the family escaped. With French assistance, Nguyễn Ánh gathered an army and returned to Vietnam. By 1802, he had not only reconquered the south but had also taken control of the north, uniting Vietnam for the first time in centuries. Establishing his capital at Huế, he quickly became suspicious of his French allies. His successors persecuted the Catholics and the French missionaries. Several executions in the 1830s prompted calls for French intervention from the nation’s Catholic population. A bombardment in 1847 did not deter the Vietnamese rulers, and in 1858 a full-scale French invasion occupied the city of Da Nang. Over the next few decades, the French expanded their rule. Saigon fell in 1861, and the rest of the south fell in 1867. Northern Vietnam fell in 1883. Southern Vietnam was renamed Cochin China, the central region was named Annam, and the north given the name Tonkin.

While they consolidated Vietnam, the French advanced into neighboring nations. In 1887, the French consolidated all three parts of Vietnam and the nation of Cambodia into the Indochinese Union. In 1893, Laos was added to the union as well.

France developed a Western system of education throughout its colonies, continued to propagate Roman Catholicism, and developed a plantation economy to promote the export of tobacco, indigo, tea, and coffee. French settlers moved mostly into southern Vietnam and based themselves around the city of Saigon. In Saigon, many Western-style buildings were constructed in reflection of the growing French population. The French attempted to spread their power over the entire countryside, but – like most empires – were exploitive of their colonial population. As such, the native population periodically rose in rebellion against the French. Though these revolts were brutally put down, the French could not root out rising nationalist sentiment entirely.

Background to War

It was in this environment of suppression and dissidence that Nguyễn Tất Thành was born. Thành, who would one day be known as Ho Chi Minh, studied in Paris and adopted a form of nationalism based in Marxist Leninism. Although he was quickly seeing communist nationalism as the only path towards independence in Vietnam, the young Ho did appeal to Western democracy for aid: after the First World War, at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Ho penned a personal appeal to President Woodrow Wilson to consider the plight of the Vietnamese people. Wilson never responded.

As Vietnamese nationalism grew in power alongside rising nationalism throughout the European colonial world, Ho Chi Minh developed a strong communist party in Vietnam. While the French opposed him and other nationalists, they quickly had larger problems to deal with. War with Germany in September 1939 gave way to a German invasion in May 1940. France surrendered to this lightning attack in June. Soon after, in September 1940, Japanese forces invaded French Indochina. Over the course of the war, the Japanese would come to occupy all of Vietnam.

A national liberation movement formed under the direction of Ho Chi Minh to combat the French and the occupying Japanese forces. The Viet Minh, as they were known, coordinated their efforts with Allied troops (including the American Office of Strategic Services, the OSS, the precursor to the CIA) fighting in the war’s Pacific Theater until the eventual defeat of Japan in 1945. After the war, the Viet Minh moved to the city of Hanoi in northern Vietnam and proclaimed national independence under a provisional government – a move that would lead to the outbreak of the First Indochina War (1946-1954) as France sought to reclaim its colony.

Backed by communist governments in the Soviet Union and the newly formed People’s Republic of China, the Viet Minh held their ground. In 1950, the fighting escalated to become a Cold War crisis as the Korean War raged to the north. With the collapse of French forces at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, France was dealt a fatal blow in the war. Still, the French held considerable power and the support of the West, including the United States. At the Geneva Conference of 1954, an accord was reached with the hope of finding a peaceful resolution, calling for the separation of Vietnam at the 17th parallel with French loyalists moving to the south and communist sympathizers moving to the north. The Geneva Accords stipulated that Vietnam be reunified by a national election in 1956, but as unification efforts stalled and Cold War tensions continued to build, these elections were never held. Additionally, the United States became increasingly involved during this time. In addition to contributing equipment and millions of dollars in financial aid, the U.S. soon deployed a contingent of non-combat personnel with its Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) to train Republic of Vietnam (RVN) forces and to oppose the spread of communism into South Vietnam.

With the Soviet Union similarly supporting its communist allies in North Vietnam – officially called the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) – and stepping up its Cold War rhetoric with the U.S. government, tensions continued to mount over the next several years. In early August 1964, the controversial Gulf of Tonkin incidents – during which the United States alleged two separate confrontations with the North Vietnamese navy, including an unprompted attack on USS Maddox by a trio of torpedo boats – gave the impetus for the passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution by Congress, enabling President Lyndon Johnson to authorize direct military action without a formal declaration of war.

Prelude to American Involvement

Throughout 1965, American involvement in Vietnam would escalate as troop levels reached new highs every month. President Johnson led the nation on a different path, opting for combat involvement over the assistance and training of South Vietnamese forces. This escalation ultimately led to the pivotal Battle of Ia Drang Valley in November. Convinced of their superiority in battle and the necessity of their mission, the United States would fully commit to the war in Vietnam.

With this context in mind, it is easy to see how the North Vietnamese push for unification was a continuation of a decades long struggle for independence. The Vietnamese people had long suffered under foreign rule, and French domination was simply the last time a foreign power would claim direct control over the nation. Nevertheless, the struggle of the Vietnamese people was being led by a communist army that tortured, executed, and extorted the local population. Upon taking control in North Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh oversaw a series of land reforms and consolidation efforts that left many dead. In their fight to unite the nation, the Viet Cong and People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN, or NVA) committed many atrocities. The United States, fearful of communist aggression and advancement in Vietnam – and unwilling to concede any advantage to Moscow and Beijing – placed itself between North Vietnam and their hope for unified, communist nation. While the American mission had a larger strategic purpose and did protect many South Vietnamese who genuinely feared communism, for many Vietnamese the United States simply replaced the French. The Fall of Saigon in 1975 represented the end of the unification struggle, and the culminating effort of nearly a century of Vietnamese nationalists.