Tuskegee Airmen

Tuskegee Airmen (1940-1952)

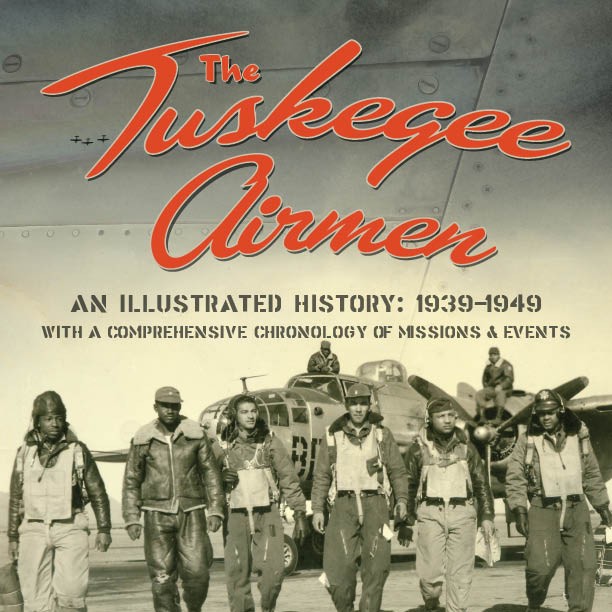

The Tuskegee Airmen was the name given to the group of African American pilots trained at Moton Field near Tuskegee, Alabama during World War II. They were the first African American military aviators and were subject to racial discrimination. However, after achieving honor and fame, they helped end racial discrimination and segregation in the United States Military.

At the time of their training, the American military was very segregated; all semi-skilled and skilled jobs went to white soldiers while African Americans were regulated to menial jobs.

The Tuskegee Airmen formed the 332nd Fighter Group and the 447th Bombardment Group of the United States Army Air Forces during 1941. The 447th Bombardment Group never saw combat, despite being well trained. The 99th Fighter Squadron was officially the first African American flying squadron and was deployed overseas in 1944, to North Africa, Sicily and Italy.

The 332nd Fighter Group began flying heavy bomber escort missions in July 1944. They became famous for having the smallest amount of escort bombers shot down under their protection. The most common airplane they flew was the P-51 Mustang. They painted the tails of these planes red, which resulted in the nicknames "Red Tails" and "Red-Tail Angels," which became synonymous with the Tuskegee Airmen.

Numerous awards and medals were given to the Tuskegee Airmen as a result of their bravery and excellence in flying. These awards and medals included: 3 Distinguished Unit Citations, 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 14 Bronze Stars, 744 Air Medals, 8 Purple Hearts, and 1 Silver Star. The group as a whole was honored in 2007 with the Congressional Gold Medal.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt specifically requested one of the Tuskegee Airmen to be her pilot on one occasion. At the end of the flight, she told the pilot, "Well, you can fly alright."

The Tuskegee Airmen played a large role in aiding the U.S. Military to welcome an end to racial discrimination. They also accomplished racial equality during the war both inside and outside military forces. The ended their duties in 1952, after achieving fame, excellence, and the beginning of the end of racial discrimination on the U.S. Military.