Record date:

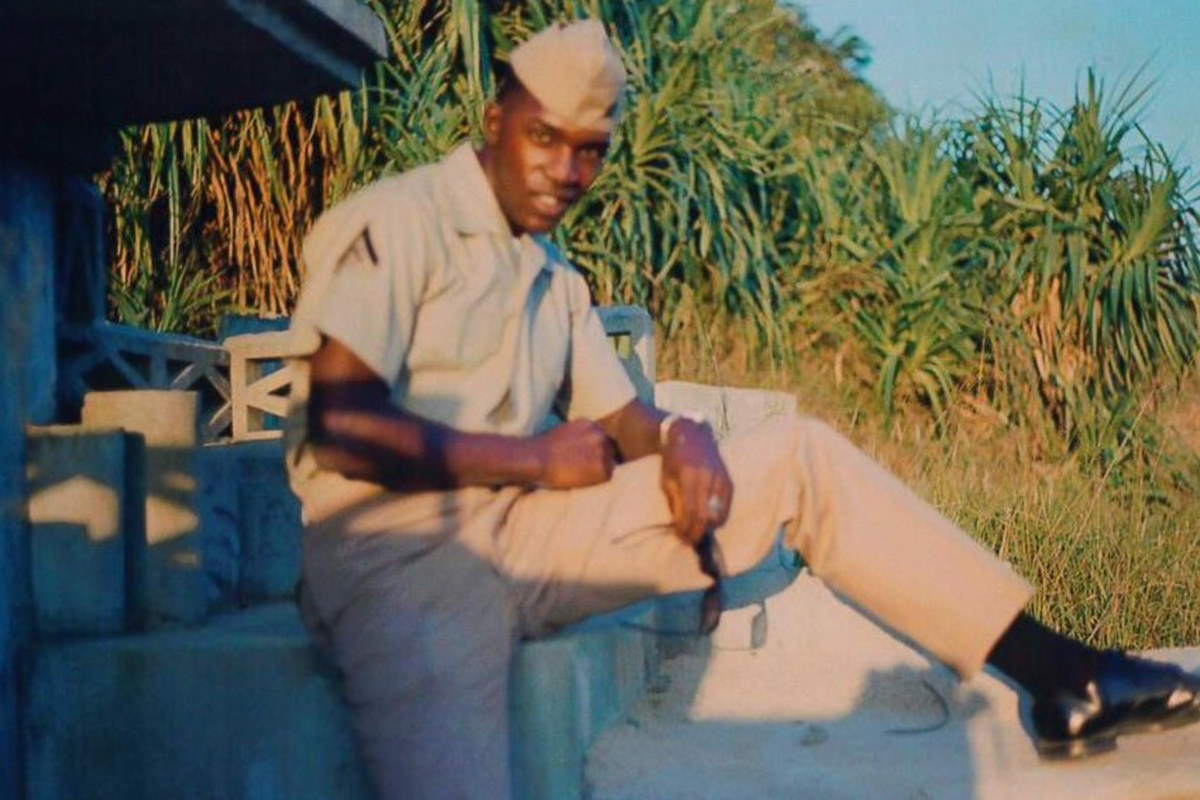

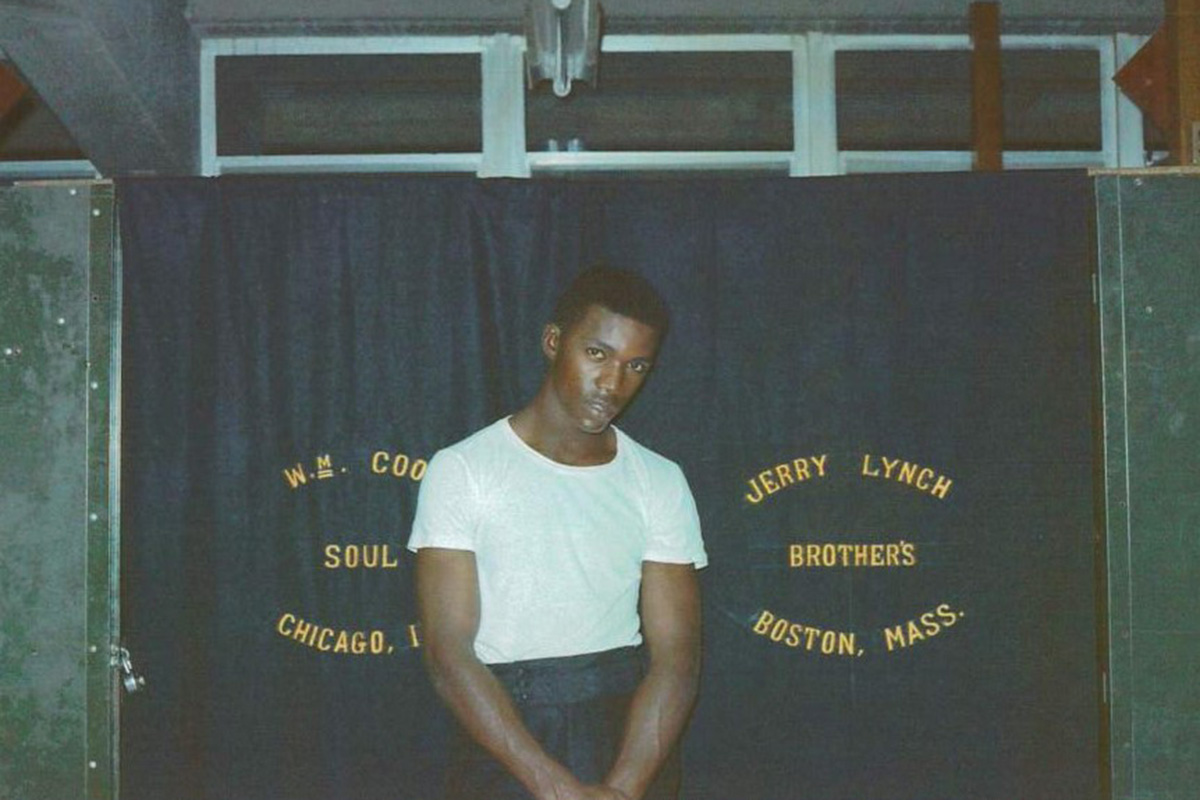

William Xavier Cook, Corporal, US Marines

While in a polarized world, one often thinks in binary terms: soldier/civilian; Black/White, Corporal William Cook presents a more integrated and nuanced view in his oral history.

Born and raised on the South Side of Chicago in 1950s, Cook grew up in a stable and close-knit community. Influenced by his father and his uncles who loved jazz and Be-Bop, William, enjoyed many a musical luminary, such as Smokey Robinson, at the Regal Theater, a popular night club among African Americans. Yet, the building of the Dan Ryan Expressway in 1961, split up the neighborhood. His family, who had the means to move, was the first Black family on their block, on the other side of Halsted St. Within two years all the Whites moved out. This may have been William’s first lesson on the limits of ‘enforced’ integration.

Cook was also aware of the active struggle for Civil Rights from early on. Even the funeral for Emmett Till, the fourteen-year-old African American boy who was lynched in Mississippi, in 1955, when visiting relatives, took place right near his home. He also reflects on the March on Washington in 1963.

As a patriotic eighteen-year-old, Cook felt horrified by what he saw on television: Americans getting killed in the Vietnam War. He therefore decided to enlist in the US Marine Corps, wishing to contribute to the goal of equality through his military service. He strived to show, by personal example, that Blacks were as equally courageous and tough as Whites and thus deserving of equal rights.

Basic training at Camp Pendleton, California required adjustment, but he rose in rank to a private first class right away. His leadership was put to the mettle when he successfully ensured that everyone would complete a five-mile hike, laden with full gear.

Although Integration of the Armed Forces had begun years before, Cook was one out of only six Blacks in a platoon of eighty-five men. After the assassination of Martin Luther King, Cook was deeply offended by a racist White expressing pleasure at this act. He hit the man and was sent briefly to the brig, but the officer saw his worth, and urged Cook to be resolute.

Although Cook wished “to see action,” the Marines were badly in need of Cook’s organizational skills. From advanced infantry, he was assigned to the supply administration warehouse, and from there was deployed to Camp Hansen in Okinawa, Japan. Even his formal request to be transferred from Okinawa to Vietnam to be with the rest of his platoon, was denied.

Cook’s commanding officer made it clear that his duty as a Marine is to serve where he is needed. He then reconciled himself and on a riff on the Marine Corps mantra, he lived by “Assess, Adapt, and Overcome.” He thus addressed the challenges of an improperly set-up warehouse - missing tools, and missing vehicle parts.

At first, Cook procured parts by trading with other US service forces’ repair shops in the area. Soon after, he taught himself to use what was then innovative technology - the IBM key punch card system. This allowed him to order parts from the main supply center in Philadelphia. He utilized his knowledge of mechanics of to identify the suitable parts in catalogues and kept track of these items. Cook also set up a system of records indicating which vehicle parts were missing and when a vehicle was ready for use.

Thus the shop succeeded in turning out vehicles returning to Vietnam on a regular basis. The commanding general was so impressed that he invited a crew from the Stars and Stripes to write an article about the provisional maintenance battalion. Cook was both photographed and interviewed for this article and promoted to E-4 corporal at this assignment.

Corporal Cook recounts the constant demand for parts for the two-and-a-half-ton truck, the “workhorse of the Vietnam War.” The majority of trucks sent to Okinawa were damaged due to road accidents in contrast to the ones damaged in combat which were usually beyond repair. Some trucks were sprayed with Agent Orange.

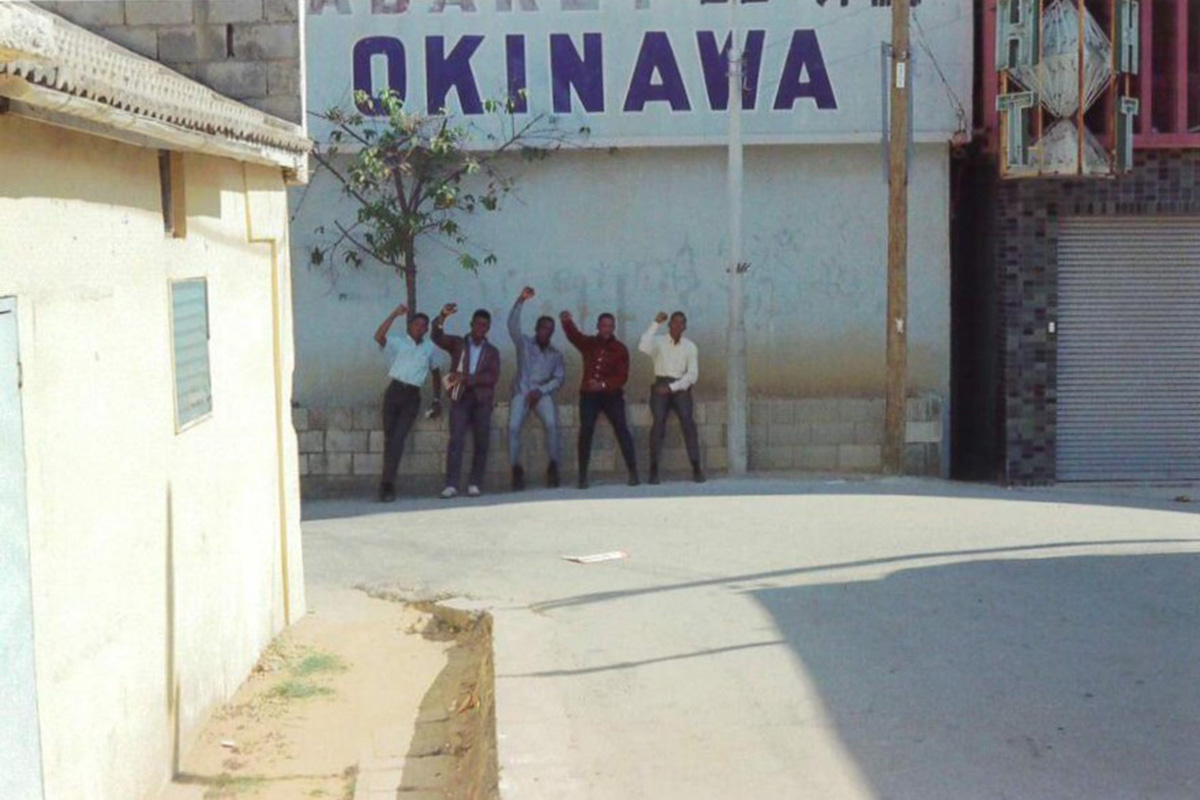

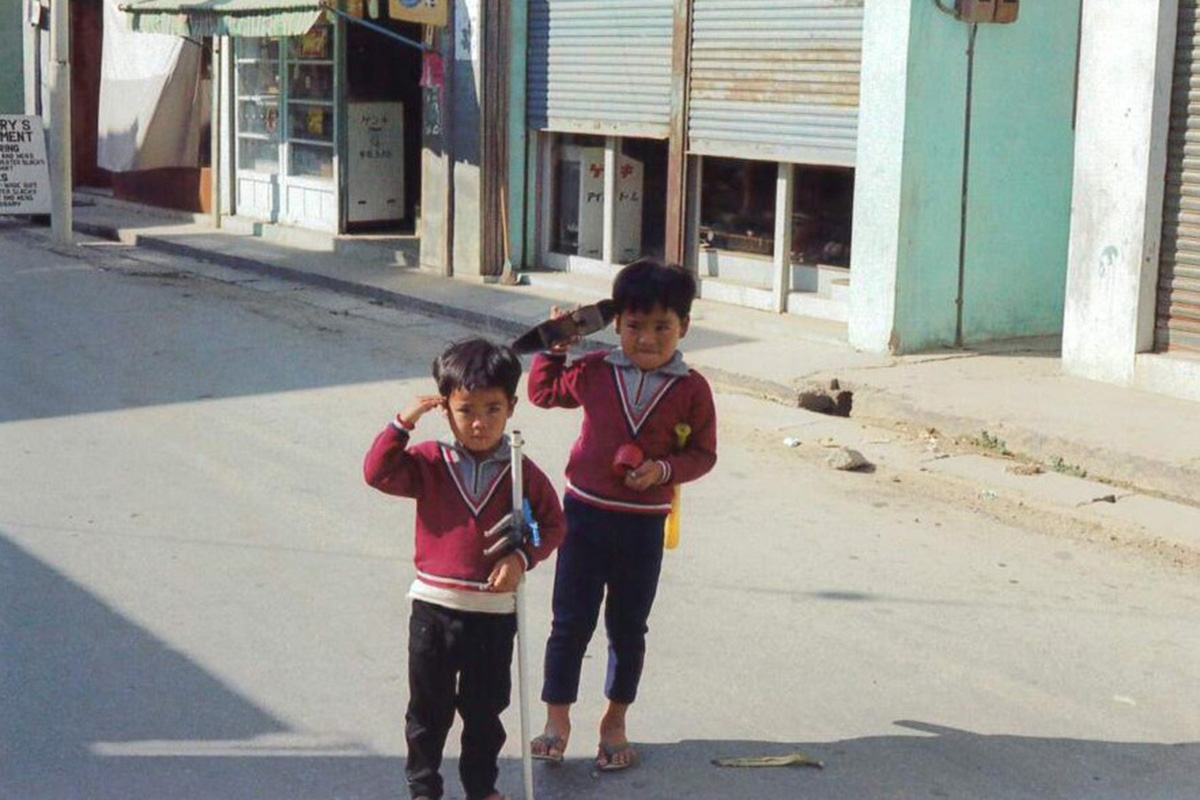

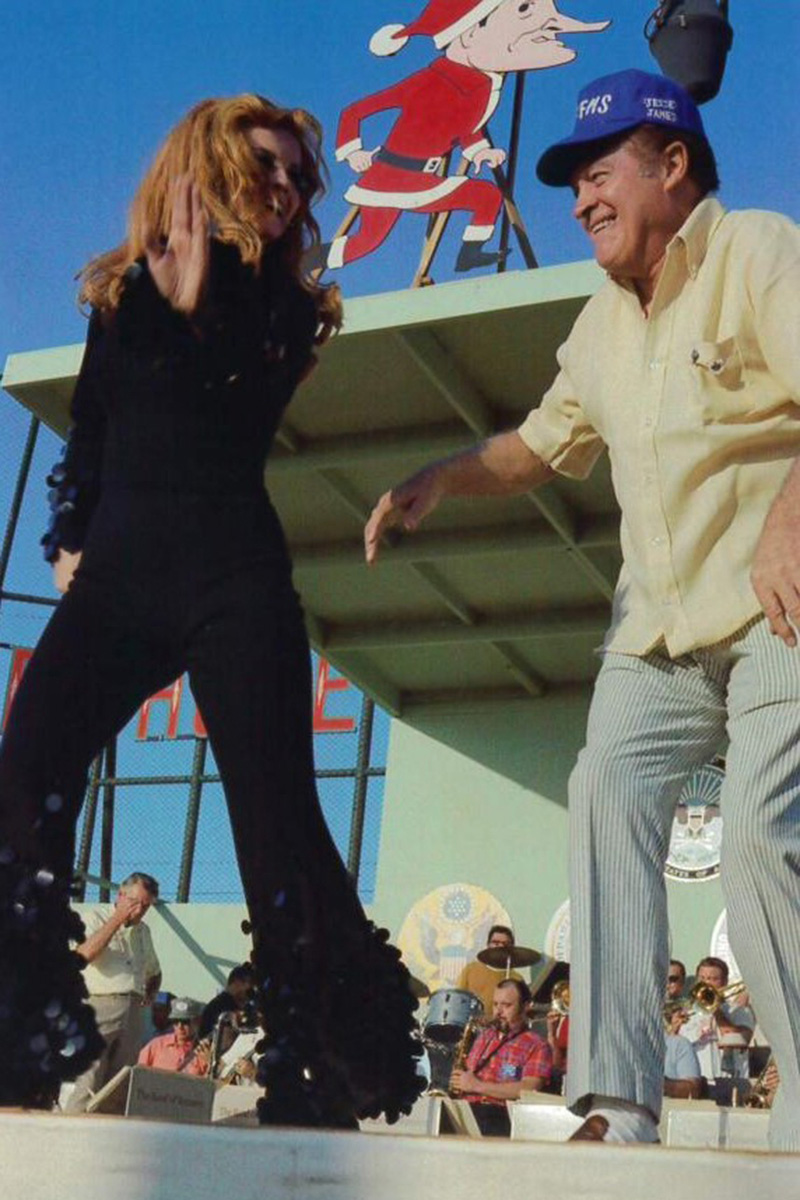

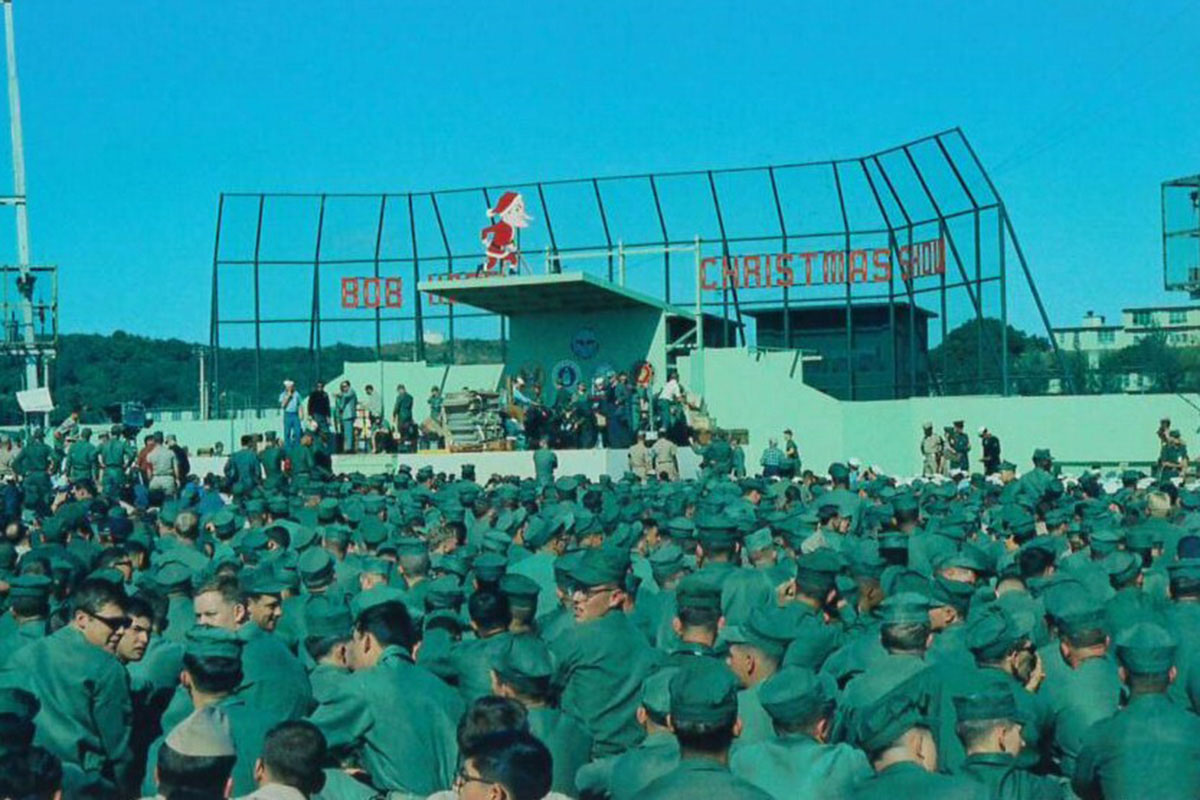

Life in Okinawa was pleasant. Although food at the base was not good, being so close to Kim Village, allowed Cook to go to restaurants there. He even found hard to come-by jazz records there. He also bought a bike and camera and enjoyed taking photos of local sites as well as the Bob Hope Christmas show of 1968. Cook also noted that although the Okinawans were grateful for the economic benefits the numerous US bases provided, they did resent US governing of the island at the time.

Cook was discharged in 1971. In addition to learning specific skills such as driving trucks, he learned invaluable life lessons: discipline, organization, and leadership.

When he returned to Chicago, Cook went to work for twenty-five years for the Post Office. He then returned to school and graduated as a paralegal and as a result of his success, was recruited to work at the DAV [Disabled American Veterans].

While working at the DAV in Phoenix, he read an article about Oscar Palmer Austin, a Black US Marine, who died before his 20th birthday who was the first Black man to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor (posthumously). Cook sees in Austin, who sacrificed his life for his fellow Marines and his country, as well as in others such as Milton Olive, a Chicago native who was a paratrooper in Vietnam and received a Congressional Medal of Honor, as models of honor and fidelity. Cook understands that not everyone can serve in the military, but even performing small acts of kindness is service to our nation, as well as good citizenship. Sending cards and letters to ill and wounded veterans at Great Lakes Naval Hospital has a significant and uplifting impact.

Cook objects to critical race theory as understood by those who want to silence the teaching of systemic racism in the US, arguing that it would cultivate feelings of guilt among Whites. Rather, Americans should learn the total history, both good and bad. It is the moral integrity of individuals, regardless of skin color, whom we want the young to emulate.

He also calls on the public to honor the citizen soldier:

“These are the…people who are going to stand up for America. These are the same individuals who are willing to leave family and friends and loved ones to risk their lives.”